Michel Tapié was not entirely one of those critics who, by putting their signature to manifestos nowadays historic, irrevocably took their place in the pantheon of art criticism. How are we to define the multifaceted activity of Michel Tapié, who seemed to prefer the sensational event to the monument?

Of all the adventurers, discoverers of artists, and writers on art of the second half of the twentieth century, both French and international, Michel Tapié is not only the one who transformed the profession by adding to the traditional activities of this role other activities (artistic adviser, publisher, broker, collector), but he is also the only one who could boast over 180 artists in his ‘stable’. Of course, it might be objected that of these, proportionally few have passed into posterity. But among the impressive number of artists who made up his stable, a few knew unprecedented success; today their works are to be found in the most illustrious collections and on the walls of modern art museums the world over, and the names of d’Appel, de Kooning, Dubuffet, Fautrier, Fontana, Francis, Hartung, Mathieu, Michaux, Pollock, Riopelle, Shiraga, Wols, and others, bore (at least for a moment) the stamp of Michel Tapié. Who else but Michel Tapié could declare ‘I am informal art’? Charles Estienne and Jean Paulhan tried, but in vain.

The following lines, written in 1938 to his wife Simone, marked as much by enthusiasm as by uncertainties, are those of a young provincial who left the Tarn, the land of his birth, to become a jazz musician in Paris, convinced of his fame to come:

I am so technically competent that I have great confidence, but I feel so incompetent the moment the question of business arises, I don’t have the strength to act alone.[i]

They are not without an echo of the numerous remarks that he will address to the gallery-owning partners he would count on to realise and financially manage his dream: the theoretical and commercial system of ‘art autre’, of which he is the inventor.

To start with, there is nothing of the businessman about Michel Tapié de Céleyran. Born into one of the most ancient families of the Languedoc, the house of Toulouse-Lautrec,[ii] he is the only member of the family who has to work for a living. Bolstered by the hopes of his parents (aristocrats who knew nothing of Parisian life and were themselves poor managers of their illustrious family heritage), Michel Tapié, self-taught musician,[iii] is already aware of his limits when it comes to such questions of money, which are beyond him. But if he certainly does not possess the qualities of financial manager, nonetheless his disinhibition in relation to the necessity to make a career, his outgoing personality inherited from his aristocratic lineage, his thirst for adventure, and finally his eye, made of this dreamer the known and recognised art critic, artistic adviser, and collector whose stratagems are on many occasions well served by his candour.

On 14 August 1948 Jean Dubuffet is not mistaken when he describes the charisma of his neighbour Michel Tapié – whom he met during the winter of 1945 when the latter moved into his studio at 114bis Rue Vaugirard in Montparnasse. Sharing as they did a common passion for art and literature, the two strike up a friendship and Jean Dubuffet is able to savour the infectious enthusiasm of his new friend, as he expresses in a letter to Gaston Chaissac:

He knows how to talk about things, with an infectious enthusiasm, and he sees a lot of people, and he has the gift of inspiring interest and sympathy in everybody.

It is this sociability, a disconcerting facility in forming relationships in the Parisian world of art and society, that seduces Jean Dubuffet. He will write:

As singular patronymics, to those such as Agamemnon and Anacreon must be added M. Magnificat, Parisian grand financier, and M. Carissimo, rich Roubaix wool merchant. It is of course Michel Tapié who knows people with such singular names.[iv]

These unquestionable qualities that Dubuffet sees as being a major asset lead him to advise Tapié to give up music in favour of writing about art. Tapié is willing to listen and is happy to follow his advice – after all, up to then music has scarcely enabled him to make a living. So he accompanies Dubuffet on visits to exhibitions, one of which will play a determining role: his visit in October 1945 to the exhibition entitled ‘Otages’ of the works of Jean Fautrier, with André Malraux writing the preface. Michel Tapié is ‘impassioned’.[v] This exhibition marks a cut-off point in the history of abstraction, which is no longer only geometric. It also constitutes a fundamental event for Michel Tapié, who is from then on convinced that it is he who must defend this new form of painting.

From this time on, Jean Dubuffet has no hesitation in welcoming him into his prestigious intellectual circle revolving around the emblematic figure of Gaston Gallimard: Georges Limbour, his childhood friend and other acquaintances met during the war; Jean Paulhan, former director of La Nouvelle Revue française; Joë Bousquet, collector; Jean Cassou, former assistant curator at the Musée National d’Art Moderne; the novelist André Malraux; the editor Pierre Seghers; Marcel Arland, writer of critical articles at the NRF; Louis Parrot, contributor to the publishing house Les Éditions de Minuit; the poet Francis Ponge; Raymond Queneau, the writer and reader at the publishing house Gallimard; and Charles Ratton, director of a gallery specialising in primitive art, Rue Marignan. Moreover, Jean Dubuffet introduces him to René Drouin, owner and director of the gallery of the same name in the Place Vendôme, for which Tapié will become artistic adviser in 1947. Before this, Jean Dubuffet entrusts him with editing the catalogue for his exhibition ‘Mirobolus Macadam et Cie ’, which opens in June 1946 in this same gallery. This first publication leads him to write a series of articles in Juin, a political, economic, and literary weekly[vi] [Photograph 3]. His career as a writer on art has taken off at last. And, on 15 November 1947, when he opens Le Foyer d’Art Brut in the basement of the René Drouin Gallery, Jean Dubuffet can leave the next day in all tranquillity for Algiers, El-Goléa, and Tamanrasset, where he spends Christmas. He hands over the keys and the reins of the Foyer de l’Art Brut to Michel Tapié, who has proved his efficiency. In fact, he has just introduced him to the medallions of Henri Salingardes. This discovery leads the young ‘temporary’ director of the Foyer de l’Art Brut to further things, so he becomes a talent hunter and in no time has demonstrated the full acuteness of his expert eye. When he discovers the work of the Frenchman Xavier Parguey, the Czechoslovakian Jan Krizek, and the Spaniard Miguel Hernández, Jean Dubuffet congratulates him:

I’m enchanted by the news from l’Institut de l’Art Brut. Congratulations! I can’t wait to get back to Paris to see it all. You seem to have made some very interesting discoveries. I have just today received your two catalogues. Hernández is extremely interesting.

Overawed by his protégé’s discoveries, though not without his jealousy having been aroused, Jean Dubuffet compliments him in a letter that conceals all the acrimony which will ultimately push him to distance himself from the world of Art Brut less than a year later, when the Foyer de l’Art becomes a not-for-profit association (11 October 1948):

I am bowled over by your drive and by your discoveries and I warmly congratulate you.[vii]

It is also his eye and his outgoing personality that lead Michel Tapié to become friends with Georges Mathieu, whom he meets at the Wols exhibition opening at the René Drouin Gallery on 23 May 1947. At the time he is a young man of twenty-six, director of public relations and publicity for the shipping company United States Lines in Paris and painter in his spare time. He is rapidly seduced by Tapié’s illustrious lineage – ‘one of the oldest families of the Languedoc’, he will later write.[viii] Soon the two join forces in order to defend lyrical abstraction and counteract the geometric abstraction, neo-constructivism, and abstraction-création that Mathieu cannot bear. The gestural painter will set in place three ‘combat exhibitions’ – showing artists with whom Tapié will soon start working:[ix] ‘L’Imaginaire’, organised with Camille Bryen (at the Galerie du Luxembourg, directed by Eva Philippe),[x] which brings together fourteen non-geometric abstract artists;[xi] ‘H.W.P.S.M.T.B’ (at the Colette Allendy Gallery),[xii] whose title is made up of the initials of the surnames of the artists;[xiii] and ‘White and Black’, the third combat exhibition (at the Galerie des Deux-Îles,[xiv] directed by Florence Bank).

After these three exhibitions, where Mathieu emerges as the leader of the new abstraction, the painter decides to stop organising combat exhibitions, thus leaving the space free for Michel Tapié, who continues to promote the form of abstraction that the critics have baptised ‘lyrical’ and, at the same time, the paintings of Mathieu, who becomes his trailblazer.

And it is through his activities in defence of Mathieu that he decides to make himself known abroad as an artistic adviser and exhibition organiser. He loses no time in contacting Alexandre Iolas, the director of the Hugo Gallery in New York, who confesses in one of his letters that he will trust Tapié’s judgement:

I’m so excited by the possibility of collaborating with you and exhibiting Mathieu, whom I like very much, and I hope everything comes off […] as I have complete confidence in your taste.[xv]

Here Tapié is using what will become his method: every time he meets an artist, collector, or dealer, he strikes up an epistolary relationship. These letters²² have two objectives: to constitute a network of relations, and to provide information on the exhibitions he will orchestrate. The method is not without bearing fruits, because his name is already doing the rounds of New York before he even gets there. Iolas moreover rises to the bait in conveying to him the degree of confidence that he has in his taste. Michel Tapié thus creates for himself an aura at a distance as well as an address book for which international gallerists will employ him. From this point on, his eye is recognised by his contemporaries and little by little his name becomes a label for those painters bearing the stamp ‘Tapié’.

But this is not his only asset. Michel Tapié also looks to his artists committed to the cause of lyrical abstraction in order to make new discoveries. So it is that when, in January 1951, Georges Mathieu is invited to visit the Milanese collector Frua de Angeli at his villa in Positano, he becomes a precious eye for Tapié, who is not free to go along. In fact, Mathieu takes advantage of this visit to go on a tour of Italy, and thus meets the painter Giuseppe Capogrossi, by whose works he is seduced – and he communicates his enthusiasm to Tapié. Two months later, Capogrossi’s works are included in a manifesto exhibition, ‘Véhémences confrontées,’[xvi] organised by Tapié and shown at the Nina Dausset Gallery, 19 Rue du Dragon. The catalogue will give rise to the term ‘art informel’, coined by Michel Tapié.

Subsequently, in the summer of 1951, he is taken on with a salary by the photographer Paul Facchetti at his studio of the same name, 17 Rue de Lille, Paris, initially in order to look after his art publications. On Mathieu’s advice, the director of the premises puts at Tapié’s disposal a space for his activities as an art dealer. To begin with, he is self-employed in this, but the gallery is rapidly looked after by the Facchetti couple, who turn the studio into a veritable art laboratory. And so, Tapié becomes an employee of the gallery in the role of artistic adviser.

Tapié has every reason to develop stratagems to make Mathieu known and to keep him in tow, as he did to continue his prospections, as he confirms in the following words addressed to his sculptor friend Maria Martins in his comments at the first hanging at the studio on 9 July 1951, where, displayed on the walls, were works by Picabia, Dubuffet, Fautrier, Mathieu, Michaux, Riopelle, Serpan, Ubac, Ossorio, and Maria Martins:

Mathieu is doing well and I must do everything possible to hang on to him and then give him a little contract. I foresee a very great future for him; Malraux holds him in high regard and he is loved by one and all; Serpan is my latest discovery and he has immediately found favour with difficult people like M. Frua de Angeli and M. Catton Rich.[xvii]

Thus, working at the Studio Facchetti not only enables him to develop his constellation of artists by constantly finding new talents whom he brings together around the core group comprising the artists present for the first combat exhibitions, but also to consolidate his innovative vision in the role of artistic adviser to a Parisian gallery. In fact, he very quickly turns towards American artists, to whom he writes numerous letters aimed at making himself known and dazzling them by emphasising the modernity of his approach, the better to attract them. He even goes so far as to write to Jackson Pollock:

I will keep you informed of developments in this activity, which I aim to make very different from the norm of art galleries but based on my experience, which has proved to me that it is necessary to change certain aspects of practices that may have been effective twenty or thirty years ago but which seem completely out of date today.[xviii]

In order to try to forge links with American artists, he takes advantage of an encounter six months earlier, when he was still at the René Drouin Gallery. Michel Tapié had received a visit from Alfonso Ossorio, an American artist of Philippine origin and a collector of works by Jackson Pollock, among others. At that moment he wanted to acquire a Dubuffet painting. Tapié was attracted both by his opinion of the works of Dubuffet and by his talent as an artist. He writes to Dubuffet:

I am also very interested in Ossorio’s work, and I asked him to leave me a few of the works that he showed me for a few days so that I can ponder over them.[xix]

Six months later, the first Parisian exhibition of the works of Alfonso Ossorio opens at the Studio Facchetti: it is a success and influential reviewers write about it. Thomas Hess, the manager of the American monthly The Arts News, visits the exhibition, as does Betty Parsons. This is the opportunity for Tapié to establish a business relationship with the New York gallery owner considered to be the symbol of the new art. And indeed, she has attracted Clyfford Still, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman, showing them in a large modern architectural space designed to showcase large-scale works.

At the Studio Facchetti, Tapié’s idea is to adopt the American method without yet having been to the United States. He shows exclusively living artists and mixes young American painters so far little known in France with his European artists. He promotes his exhibitions very widely and conceives them as veritable ‘happenings’. Tapié sees America as a promised land. He quivers in anticipation:

If only I could develop contacts both here and in New York, where so many things are happening!

However, although he waits for more than five years – until December 1956 – before finally going there, this doesn’t prevent him from making contacts, at a distance, via the expert and complicit eye of Jean Dubuffet, starting in October 1951. Accompanied by his wife Lili and Alfonso Ossorio, Dubuffet is totally overwhelmed by New York and Chicago and, filled with optimism for the roles of art critic and artistic adviser, sends Tapié gallery owners, artists, and collectors. Glasco, Pollock, and de Kooning are revelations, whose work he sends photos of to Michel Tapié, who in turn wastes no time in including them in his constellation by showing them in his exhibitions.

It is in the Studio Facchetti that Michel Tapié, with the help of Ossorio, organises Jackson Pollock’s[xx] first Paris exhibition, which will have considerable impact and which Michel Tapié will constantly talk about.

It is at the Studio Facchetti that his manifesto-work, Un art autre où il s’agit de Nouveaux dévidages du réel, will be unveiled. Its aim is to ‘theorise’ the aesthetic that is common to the works that he brings together under the banner of ‘art informel’. The book Un art autre proposes a new response to the debates between the partisans of abstraction and those of figuration, and offers a means of going beyond national frontiers because it defends forty-two international artists. The ideology it develops will form the basis of the commercial system that Michel Tapié is beginning to put in place. It is intuitive and personal and does not establish any real criterion that might lead to a clear definition of ‘art informel’. Killing two birds with one stone, this publication establishes both the myth of his invention of ‘art informel’ and that of his persona. In fact, by making of his intuition an indicator according to which he can – or not – attribute this label to a work that he ‘receives’, ‘art informel’ becomes intrinsically linked to the personality of Michel Tapié. This leads to a shutting-off of the label ‘art informel’ which, implicitly, can only be delivered by Michel Tapié.

Having completed the manuscript in August 1952, on his second visit to the twenty-sixth Venice Biennale, Michel Tapié publishes his book at the beginning of December 1952. It is presented at an exhibition of the same name organised at the Studio Facchetti,[xxi] which the cream of Parisian society and personalities of the international art world such as Sidney Janis and Darthea Speyer rush to see.

The ‘art autre’ system is on the move.

Following upon his activities at the Studio Facchetti, Michel Tapié works as artistic adviser to several galleries, in France and abroad. Two galleries open successively in Paris: the Rive Droite Gallery and the Stadler Gallery.

Like Paul Facchetti, the directors of these galleries, Jean Larcade and Rodolphe Stadler, start off as art dealers. They ask Tapié to guide the artistic choices of their galleries and to create communication links between the artist, the dealer, and the collectors. Given that Michel Tapié was always short of money and an amateur as a manager, it is understandable that he sought the support of dealers who financed the career he had always dreamt of. In 1954, shortly after he was taken on for fifteen years by Rodolphe Stadler, and while still working for the Rive Droite Gallery, Michel Tapié, now aged forty-five, has already approached the Zoe Dusanne Gallery (Seattle), with whom he sketches out a few plans; has shared a project with the Evrard Gallery (Lille); has allied himself with the Spazio Gallery (Milan) directed by Luigi Moretti (architect); and has, for a short time, been advising the Martha Jackson Gallery (New York). With the latter, he embarks on a ‘grand-style secret manoeuver whereby by paying more money she would get more contracts for her gallery’.[xxii]

His aim being to build a stock of the best works by the best artists, Michel Tapié orchestrates a real dealer system. He takes the lead of a veritable coalition of galleries who join forces (their finances) to multiply his chances of offering the biggest contracts to those artists of primary importance whom he can convince thanks to the international dimension of this coalition. By advising these different galleries simultaneously, Michel Tapié creates a synergy that enables him to put on travelling exhibitions. An artist of the ‘art autre’ constellation can now be sure of being exhibited in France, the United States, and Italy. Aware of having at last found his invention, he writes in a letter to Luigi Moretti:

My plan is more certain than ever. I have all the right cards in my hand […] and I can bring to fruition in the coming years a ‘business’ to rival that conducted in the twenties and thirties by the great dealers like the Rosenbergs and Paul Guillaume.[xxiii]

So Sam Francis got it right when he said to Yves Michaud on the subject of Michel Tapié, ‘He’s a very active guy, the entrepreneur type.’[xxiv] He is as much an entrepreneur as an adventurer when he roams the world in search of new artists to add to his constellation. In Italy, he sets out to meet the artists Burri, Capogrossi, Dova, Fontana, and Moreni, and gets to know the gallery owners Enzo Cortina (Cortina Gallery), Carlo Cardazzo (Galleria Del Naviglio), Beatrice Monti (Galleria dell’Ariete), and Luciano Pistoi (Notizie Gallery), with whom he will work closely. In March 1960 he will make Turin the capital of ‘art autre’ by creating – with the support of the artists Franco Assetto; Franco Garelli; Ada Minola, jewellery designer; and Ezio Gribaudo, artist and art publisher (Éditions Pozzo) – the International Centre of Aesthetic Research (ICAR) [Photograph 21]. He will put in place a programme of exhibitions for his constellation of international artists. The exhibition catalogues, published by Pozzo, will spread the thinking of ‘art autre’ in Italy.

Thus it is that Michel Tapié knows how to mobilise and create all the resources he has at his disposal (art dealers, channels of communication, art publishers, artists, collectors, and galleries) in order to realise his personal vision of art and the structures he is creating out of it throughout the Western world.

Michel Tapié makes innumerable trips to these countries which, at that very moment, are in the process of opening up to the outside world. He explains his taste for travel thus:

The facility of access to information thanks to modern solutions to problems of communication led me to take art on its own scale, which has become that of our planet, and, as an art lover, I moved into travel, first in Europe starting in 1947, and then all over the world starting at the end of 1956, visiting artists and organising exhibitions (in particular between Europe, the US and Japan), which has enabled me to take stock of art as adventure.[xxv]

In 1957, at the invitation of Antoni Tapiès and Antonio Saura, Tapié goes to Spain, to Madrid and Barcelona, where he exhibits his artists alongside Spanish artists, who from now on bear the stamp ‘art informel’.

A year earlier, when the Japanese artist Hisao Domoto mentions Gutai to Michel Tapié, the latter is interested and quickly starts up a written correspondence with Yoshihara Jiro, the leader of the Gutai group. So they organise an exhibition entitled ‘Contemporary World Art Exhibition’, which opens in November 1956 in the Takashimaya department store in Tokyo. From a distance, Michel Tapié lends a few works from his personal collection to the exhibition, which displays original artists from the ‘art autre’ constellation. This exhibition marks the arrival of ‘art informel’ in Japan and is the beginning of Michel Tapié’s fame in the country. In the exhibition catalogue, he is described as being the ‘pioneer of the movement’, and the press talks about the ‘informel cyclone’. A month later, in December 1956, the Gutai manifesto is published in the art magazine Gueijutsu Shincho, and Michel Tapié takes a number of artists from the group into his constellation. Subsequently, he goes back to Japan innumerable times and meets Atsuko Tanaka, Kazuo Shiraga, and the other members of the group. He organises numerous momentous festivals mixing international ‘informel’ artists and Gutai.

In 1970, known as he was as a promoter of ‘art autre’, he goes to Iran guided by the young artist Hossein Zenderoudi and is received by Farah Diba. For a while he is artistic adviser to the empress, while at the same time he becomes artistic adviser to the Cyrus Gallery, situated in the Maison de l’Iran (65 Champs-Élysées, Paris). The gallery shows Iranian artists that Michel Tapié associates with ‘art autre’.

As of now, the ‘art autre’ system is international. It extends across the world, and these artists whom Tapié takes into his constellation as he discovers them nurture it.

Adventurer-traveller, man of wit and invention, he knows very well how to play a double game with the artists or the art dealers with whom he works. Inclined as he is to dream up unrealistic projects – is he feigning or is he sincere? – he does not hesitate to share his dreams with artists, dealers, and collectors, sometimes sceptical, often won over. Sometimes he boldly promises international gallery owners to organise exhibitions of coveted artists and often gets the agreement of dealers seduced by the importance of improvised projects. This form of agreement, by a ricochet effect, also enables him to obtain the consent of artists who, in some cases, have never even heard of Tapié. It is thanks to this swashbuckling that important international artists, seduced by Tapié’s sometimes chimeric relations, rally round the constellation of ‘art autre’, enabling the dream to become reality. Sometimes Tapié suggests creating and financing the catalogues for exhibitions that he has proposed and then ends up sending the bill to the gallery owner who, despite having been duped, is nonetheless delighted to have been given, keys in hand, an exhibition bearing the ‘Tapié’ stamp. Sometimes he even goes as far as manoeuvring to take over the work of an artist to the detriment of even influential gallery owners. At one point Tapié made an agreement with Dubuffet to thwart the activity of his New York dealer, Pierre Matisse; he also got together with Frua de Angeli and gave him to understand that if he broke with Matisse, he would undertake to take all his work, thus squeezing out the dealer with whom Tapié nonetheless tried, but in vain, to maintain good business relations. Tapié the strategist even envisaged dealing in parallel with other galleries in order to ensure, in the event of war with Pierre Matisse, the successful distribution of Dubuffet’s work. So, to attract the sympathy of coveted artists, he went as far as to accept the plan – inventive to say the least – proposed by the New York gallery owner Martha Jackson. ‘Birds of a feather flock together’ … she proposes getting Jackson Pollock to sign a contract with Tapié. In order to do this, she suggests that the latter write to Pollock (who is on the point of leaving his dealer Sidney Janis) to invite him to the opening of the Rive Droite Gallery. Pollock is dreaming of a trip to Europe without his wife and he likes beautiful cars, so it’s the perfect opportunity to lure the artist into their net! In order to persuade him to travel to Paris, Mathieu has to offer to drive the artist to Venice and Rome in his Rolls-Royce. The plan falls through.

To conclude, Michel Tapié has moved, in a very short time, from being a young provincial, a bohemian musician, and an artist out of pique, to being a redoubtable and obstinate tactician, opportunistic artistic adviser to the biggest collectors and to dozens of international galleries.

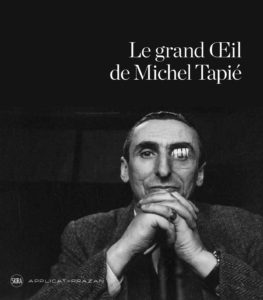

Sporting in society his cigar or his pipe as well as his monocle, giving him the air of a grand seigneur, and narrating his innumerable travels all over world to anyone willing to listen, Michel Tapié forces artists starting out in their careers and collectors and art dealers starting in the trade to concede a certain admiration. It is this aura that leads them to grant to his ‘eye’ a determining power in their career. Claude Bellegarde declared: ‘You know Tapié was a bit of a dandy, but a dandy from another century!’[xxvi]

It was no doubt this same admiration that led Paul Jenkins one day in Saint-Germain-des-Prés to come out with these inspired words to the sculptress Claire Falkenstein:

Michel Tapié is very busy in Paris and seems more active than ever. What a beautiful presence this man possesses. I was in Saint-Germain drinking a beer at the Flore; I look across the street and see Tapié at a bus stop. It was the first time I’d seen him from a distance. All I can say is what a presence his presence is. The bus could easily have been a chariot of gladiators with six white horses on the point of taking off for the sun.[xxvii]

Paul Jenkins will go so far as to write a book entitled Observations of Michel Tapié,[xxviii] bearing witness to his admiration for the art critic and artistic adviser. He will solicit the participation of his artist friends in the ‘art autre’ constellation: John Hultberg, Henri Michaux, Claire Falkenstein, Georges Mathieu, César, and Mark Tobey, who will paint Tapié’s portrait. Finally, over and above this work, a number of artists will paint or photograph the features of their mentor: Appel, Battaglia, Dubuffet, Facchetti, Falkenstein, Calder, Brown, Garelli, Gribaudo, Tapiès, Minola, Motonaga, Newman, and Lemaître.

One of the many portraits that Dubuffet painted of Tapié, Michel Tapié soleil, which is now in the Centre Pompidou, is a reminder of the extent to which this art critic, artistic adviser, and collector managed to turn his ‘master stroke’ into a durable system that spread its influence for a long moment on a world transformed by it into an international artistic scene, opening the way for other promoters of the art we know today.

Juliette Evezard

PhD in the History of Art

________________________

[i] Letter from Michel Tapié to Simone Tapié, Paris, 1938 (Tapié archives, Kandinsky Library, Paris).

[ii] The Toulouse-Lautrecs; Vicomtes de Lautrec et de Montfa, his surname; that is to say, the association of two noble houses, Toulouse and Lautrec, which has existed since 1196.

[iii] He plays five instruments: piano, vibraphone, clarinet, saxophone, and double bass.

[iv] Letter from Jean Dubuffet to Jean Paulhan, 9 June 1946, reproduced in Julien Dieudonné and Marianne Jakobi (eds), Dubuffet–Paulhan, correspondance 1944–1968, Les Cahiers de la NRF, Paris, Gallimard, 2003, pp. 302–303.

[v] Letter from Jean Dubuffet to Jean Paulhan, 27 October 1945, reproduced in Dieudonné and Jakobi, Dubuffet–Paulhan, correspondance 1944–1968 p. 244.

[vi] This weekly, the organ of the Union Nationale des Combattants des Maquis de France, was published between 19 February 1946 (date of the first issue) and 7 January 1947 (date of the forty-seventh issue).

[vii] Letter from Jean Dubuffet to Michel Tapié, 15 March 1948 (Tapié archives, Kandinsky Library, Paris).

[viii] Georges Mathieu, Au delà du Tachisme, Paris, Julliard, 1963, pp. 56–57.

[ix] Respectively for each exhibition: Brauner, Ubac, and Atlan; Wols, Hartung, Stahly, Picabia, and Fautrier; and Bryen, whom Michel Tapié will include in Un art autre (1952).

[x] From 16 December to 5 January 1947, 15 Rue Gay-Lussac, Paris, Ve.

[xi] Arp, Atlan, Brauner, Hartung, Leduc, Mathieu, Picasso, Riopelle, Solier, Ubac, Verroust, Vulliamy, and Wols.

[xii] Colette Allendy Gallery, 67 Rue de l’Assomption, Paris, XVIe.

[xiii] Hartung, Wols, Picabia, Stahly, Mathieu, Tapié, and Bryen.

[xiv] The Galerie des Deux-Îles is situated at 1 Quai aux Fleurs, in the fourth arrondissement of Paris. The exhibition opens on Monday 19 July 1948. Michel Tapié exhibits alongside Arp’s drawings, prints, and lithographs, as well as Bryen, Fautrier, Germain, Hartung, Mathieu, Picabia, Ubac and Wols.

[xv] Unpublished letter from Alexandre Iolas to Michel Tapié, 5 October 1950 (Tapié archives, Kandinsky Library Paris).

[xvi] It will be on show from 8 March 1951 until 31 March 1951.

[xvii] Unpublished letter from Michel Tapié to Maria Martins, 26 July 1951 (Tapié archives, Kandinsky Library, Paris).

[xviii] Unpublished letter from Michel Tapié to Jackson Pollock, 17 July 1951 (Tapié archives, Kandinsky Library, Paris).

[xix] Unpublished letter from Michel Tapié to Jean Dubuffet, 11 January 1951 (Tapié archives, Kandinsky Library, Paris).

[xx] This exhibition opens at the Studio Facchetti on 7 March 1952.

[xxi] It opens on 17 December 1952. It is the gallery’s fourth group exhibition after ‘Signifiants de l’informel I’, ‘Signifiant de l’informel II’, and ‘Peintures non abstraites’. Michel Tapié shows the works of Appel, Arnal, Bryen, Dubufet, Étienne-Martin, Falkenstein, Francis, Francken, Gillet, Galsco, Guiette, Kopac, Mathieu, Ossorio, Pollock, Riopelle, Ronnet, Serpan, and Wols.

[xxii] Unpublished letter from Michel Tapié to Jean Larcade, 13 August 1954 (Tapié archives, Kandinsky Library, Paris).

[xxiii] Unpublished letter from Michel Tapié to Luigi Moretti, 8 June 1954, (Tapié archives, Kandinsky Library, Paris).

[xxiv] Yves Michaux, ‘Sam Francis, Paris, années cinquante’, Art Press no. 137, July–August 1988, p. 21.

[xxv] Michel Tapié, Esthétique, Turin, International Center of Aesthetic Research, 1969.

[xxvi] Author interview with Claude Bellegarde, Neuilly, 13 October 2010.

[xxvii] Unpublished letter from Paul Jenkins to Claire Falkenstein, n.d., (Box 7, File 61, Falkenstein Papers, 1914–1997, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington).

[xxviii] Paul Jenkins, Observations of Michel Tapié, Wittenborn, New York, 1956.